Agreement criticized for imposing no sanctions on countries that fail to reduce emissions

reposted from CBC News, Dec 12, 2015

UPDATED

- Countries adopt Paris climate deal

- Pact would be legally binding, French foreign minister says

- ‘Endeavour to limit’ global temperature rise to 1.5 C

- $100B funding for developing countries by 2020

Nearly 200 nations adopted the first global pact to fight climate change on Saturday, calling on the world to collectively cut and then eliminate greenhouse gas pollution but imposing no sanctions on countries that don’t.

Loud applause erupted in the conference hall outside Paris after French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius gavelled the agreement Saturday. Some delegates started crying. Others embraced.

The countries had been negotiating the pact for four years after earlier attempts to reach such a deal failed.

- Read the agreement

- COP21: Canada’s new goal for limiting global warming ‘perhaps a dream’

- Climate talks stretch through night as deadline for historic deal looms

- New Fossil of the Day Award: Canada back in climate bad books

Shortly after the deal was adopted, Canadian Environment Minister Catherine McKenna tweeted: “History is made. For our children.”

U.S. President Barack Obama tweeted that approving this landmark deal is “huge” and touted American leadership on the issue.

The agreement, South African Environment Minister Edna Molewa said, “can map a turning point to a better and safer world.”

The deal now needs to be ratified by individual governments and would take effect in 2020.

It is the first pact to ask all countries to join the fight against global warming, representing a sea change in UN talks that previously required only wealthy nations to reduce their emissions.

‘We didn’t sleep very much’

Under the deal, countries will have to publish greenhouse gas reduction targets and revise them upward every five years, while striving to drive down their carbon output “as soon as possible.”

The final text of the agreement commits countries to keeping global warming “to well below 2 degrees C” and hopes to limit it to 1.5 C, with the goal of a carbon-neutral world sometime after 2050.

“It is my deep conviction that we have come up with an ambitious and balanced agreement,” Fabius said in introducing it Saturday morning at the closing session of the summit.

“We all worked a great deal. We didn’t sleep very much.”

The 31-page text, called the Paris Agreement, was distributed to countries for them to assess, then agreed to at a plenary session.

.@LaurentFabius "The proposed text contains elements that we thought were impossible to achieve before" #COP21 pic.twitter.com/g6jT5hQ2yW

— UN Climate Action (@UNFCCC) December 12, 2015

Fabius's warning: "children of the world would not understand us, nor would they forgive us" if they fail to ratify agreement #cbc #cop21

— Nahlah Ayed (@NahlahAyed) December 12, 2015

Fabius, flanked by French President François Hollande and UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, called the pact “a historic turning point” and said it contained some key provisions. Those include terms making the accord legally binding, as well as the 1.5 C goal — below the 2 C standard scientists say is essential to limiting potentially catastrophic climate change.

That was a key demand of developing countries ravaged by the effects of climate change and rising sea levels.

Another major debate has been over a promise that developed countries should provide $100 billion annually to help poorer states deal with the consequences of climate change. The text sets that figure as a floor by 2020.

Earlier in the day, Elizabeth May, leader of Canada’s Green Party, agreed with Fabius that the draft text was ambitious but balanced.

“Having it presented with Ban Ki-moon on one side of Laurent Fabius and the president of France, François Hollande, on the other side, very clearly they are saying, ‘This is the best we’re going to get, not just now, but probably ever. Grab it with both hands,'” May said in an interview.

“And then we start the work, which is substantial, to constantly push for greater levels of emission reductions than what we now have.”

The Green Party later tweeted its congratulations to May, McKenna and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Not far enough, critics say

Shortly after the tentative deal was introduced Saturday, thousands of protesters in Paris, under the close watch of riot police, held hands beneath the Eiffel Tower and denounced the pact as too weak to save the planet.

Danielle Lefait, a retired deaf student teacher, said she was protesting because she is afraid of the environmental risks of proposed shale gas extraction in her town of Arras in northern France. Other protesters were angry the accord didn’t do more to force governments to give up fossil fuels blamed for warming the planet.

The pact doesn’t have any mechanism to punish countries that don’t or can’t contribute toward its emissions-reduction goals.

Negotiators from more than 190 countries were in Paris to create something that’s never been done before: an agreement for all countries to reduce man-made emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases and help the poorest adapt to rising seas, fiercer weather and other impacts of global warming.

This accord marks the first time all countries are expected to pitch in — the previous emissions treaty, the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, only included rich countries. Canada signed on to Kyoto, but later backed out in 2011.

The Pembina Institute, a Canadian environmental think-tank, said Canada will only be able to meet the emissions targets under the new Paris Agreement if it brings in a national minimum standard for carbon pricing.

“On their own, provincial commitments will not ensure Canada does its fair share to reduce emissions consistent with the science of global warming,” Pembina’s federal policy director, Erin Flanagan, said in a statement.

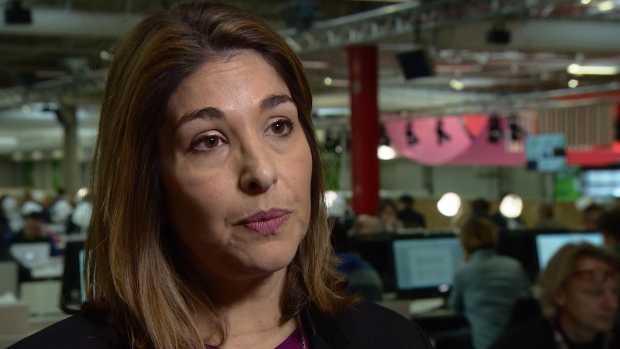

One problem with the text’s aggressive temperature targets is that the pledges countries have made so far would fail to limit global warming to even 2 C or less in the long term, Canadian activist Naomi Klein said in an interview with CBC News.

Klein also took issue with a clause that rules out any liability for climate change.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” she said, “where countries are literally fighting for their very survival, and because of that desperation they’re being asked something that they really need a lot, which is their right to seek compensation later on.

“And I think Canada backing that position is really quite immoral.”

With files from CBC’s Kyle Bakx, The Associated Press and Reuters